Qat’al Al-Hasa, a fascinating historical site located 5 km northwest of the Hejaz Railway Station, offers a glimpse into an era long past. Nestled on the south bank of the Wadi al-Hasa’s main bed, the location boasts architectural remnants that speak to both its strategic importance and the craftsmanship of a bygone era. Its main features include a large square fort, a modest reservoir, a paved roadway, and a bridge spanning the Wadi al-Hasa—all steeped in history and intrigue.

The Bridge

Constructed between 1730 and 1733, the bridge marks the oldest structure at the site. Serving as a crucial crossing point over the Wadi al-Hasa, it represents the ingenuity of engineers at the time. This stone creation would later complement the fort built in 1760, adding further strategic significance to the area.

The Fort

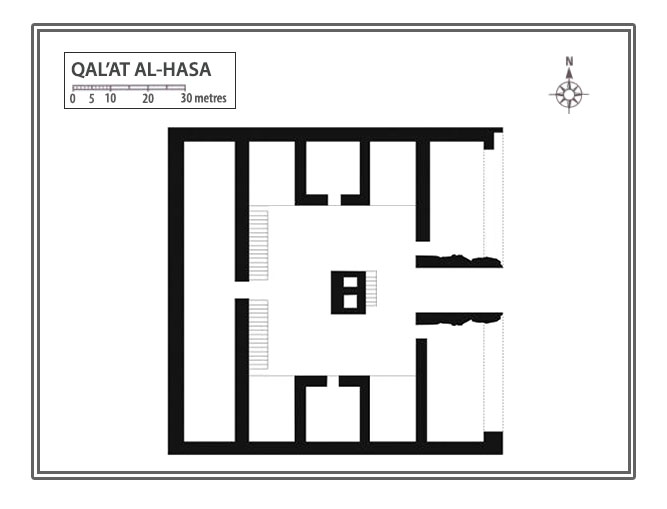

The fort stands as the centrepiece of Qat’al Al-Hasa, a bastion whose design conveys both its functional purpose and historic charm. It was constructed on a gently sloping landscape towards the south side of the Wadi, with an elevation difference of 0.7m between its north and south sides. Despite the passage of time and damage to the structure, restoration work in the late 1980s and early 1990s has preserved some of its original majesty.

The north wall, made of finely cut ashlars, offers insight into the skill of its builders, while the remaining walls—crafted from roughly hewn limestone blocks and occasional basalt pieces—delineate the fort’s perimeters. The south wall has undergone significant alteration, but an intriguing feature in its design is a series of small, slit windows and the remnants of a gallery that once projected majestically from the facade.

Intricate Design Features

The east and west walls mirror elements of the fort’s southern fortification. The east wall stands remarkably intact, featuring six small slit windows at the first-floor level and retaining one crenellation, a detail that suggests the fort’s defensive capabilities. Engaging visitors further are the iwans, or open vaults, along the courtyard’s west and east sides. These iwans, set symmetrically around a central room, add a layer of architectural sophistication to the fort’s structure.

The fort’s entrance, centred on the south wall, is covered by a slightly pointed vault crafted from flat slabs of limestone. Stepping through, visitors enter a courtyard measuring 12.5 metres on each side, revealing thoughtful planning and design. At its centre, a tall rectangular structure built over a 10-metre-deep well highlights the site’s self-sufficiency in water.

The Courtyard and Rooms

Nine rooms surround the central courtyard, each a small testament to the challenges and ingenuity of life in the fort’s heyday. Barrel-vaulted chambers, iwans, and stairs leading to other sections of the fort tell a story of day-to-day activities and defensive readiness. Particularly striking is the southern range’s first-floor layout, which features six barrel-vaulted rooms flanking a central iwan housing a plain, understated mihrab.

Though much of the upper levels have succumbed to time and the elements, fascinating glimpses remain. Two small gun slits on the south wall hint at the fort’s defensive role, while stone corbels in other areas suggest the existence of parapet walks.

The Reservoir

Located 50 metres east of the fort, the reservoir adds to the allure of Qat’al Al-Hasa. Measuring 20 metres per side, this square structure channels the resourcefulness of the past. Lined with plaster and built using squared limestone blocks, its design ensures efficient water storage. A small underground channel connects the well at the fort’s courtyard to this reservoir, highlighting the sophisticated water management system that sustained life at the site. Steps in the northwest corner descend into the reservoir, evidence of thoughtful functionality and adaptability.

Stepping Back in Time

Qat’al Al-Hasa is more than just an archaeological site—it’s a portal to an intriguing past where every detail, from the small slit windows to the vaulted iwans, whispers a story of resilience, utility, and craftsmanship. Whether you’re an architectural enthusiast or a lover of history, the site captivates the imagination, inviting visitors to walk in the footsteps of those who once called this place home.

Qal’at Al-Sasa, a historic stop along the Ottoman pilgrimage route, brings to light fascinating glimpses of the past. First mentioned in the travels of Mustapha Pasha in 1563 AD, it was a key waypoint during the era of pilgrimage caravans. By the 18th century, Murtada ibn ‘Alawan highlighted its importance, located between Qatrana and ‘Anza. Around this period, Aydinili Abdullah Pasha constructed a bridge over Wadi al-Hasa to mitigate dangerous flash floods. He is also believed to have paved the road leading to the bridge, crucial for safer travel.

The location, sometimes referred to as Tabut Korsu (‘burial grove’), is noted for being the burial site of Celaleddin Halveti. Visitors like Mehmed Edib in 1779 remarked on the bridge’s strategic significance, alongside structures such as a fort and a cistern. However, Edib also noted the challenges of limited drinking water and the presence of robbers at nearby stops like Uziyr Sultan.

By the early 19th century, repairs were noted at the site, including fixes to earthquake damage and flood-affected sections of the bridge. Later accounts in the 1860s, such as those by Christophe Mauss and Henry Sauvaire, describe a square fort with a central courtyard, surrounding storerooms, and living spaces for local guards. Adjacent to the fort were a large cistern and a two-arched bridge, alongside a small garden planted by the garrison. The paved road leading from the fort marked the edge of the desert, reminiscent of ancient Roman pathways.

A detailed archaeological survey in the 1980s, as part of the Wadi al-Hasa Archaeological Survey, further uncovered remnants of the Ottoman period. These included villages, a massive 240-metre-wide enclosure likely used for the Hajj caravan as a camping or animal corralling area, and evidence of the fort’s enduring role in the landscape.

Qal’at Al-Sasa stands as a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of those who navigated its harsh terrain centuries ago.