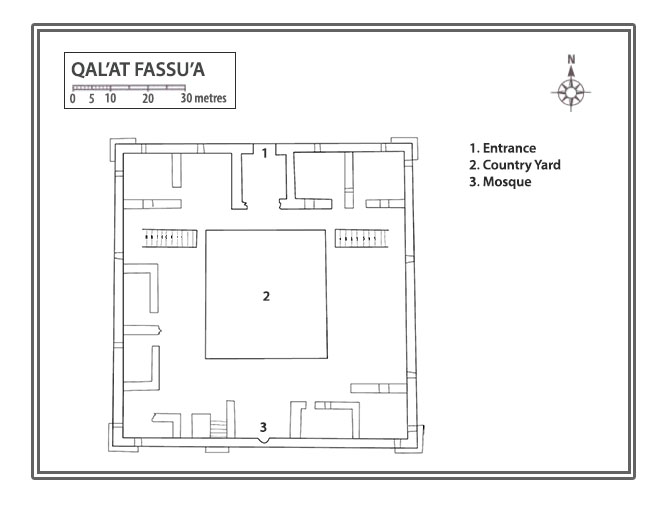

Qal’at Fassu’a is located 2 km west of Muhattat Fassu‘a, on the Hijaz railway line and consists of a fort, two reservoirs and a signal beacon. Immediately to the north of the site is Wadi al-Msas, a tributary of the Wadi Abu ‘Amid. The whole area around Fassu‘a is a high plateau, intersected by deep, precipitous gullies and, in general, may be characterized as rugged. The ground is, in general, covered by stones of flint and limestone; interspersed with the odd camel thorn bush. The location of the site is important, as it is the last fort on high ground before the route descends through Batn Ghul to the Arabian Desert.

The fort is square in plan, measuring 20 x 20 m and standing to an average height of 7 m above the surrounding ground level. It is built out of a mixture of slate, flint, basalt and limestone, roughly squared into blocks, the gaps between being filled by small flat pieces of stone. The stone blocks are held together with a lime mortar that shows evidence of repairs in many places. There are no remains of crenelations on any of the walls; instead, the walls are capped with a layer of small stones, mortared together to produce a round ridge, running all around the external walls of the fort. At each of the four corners, there is a projecting tower, set at a height of 5 m above ground level. All the towers have the same basic design.

Of similar design to these towers is a box machicolation in the middle of the south side of the fort. The structure is set into the wall of the fort at a height of 5 m above ground level. The machicolation is 2.2 m high, including the supports and the roof. The floor of the machicolation is composed of long, flat pieces of plate flint, resembling that of the corner towers, except that there are gaps between the corbels allowing it to function as a machicolation. As in the corner towers, the machicolations are roofed with heavy stone tiles, laid at an angle to the face of the fort.

There are 14 windows (four on each of the east, west and north sides and two on the south side) set into the outer walls of the fort. These openings are of very simple design, with an average height of 0.7 m and width of 0.1 m. All of the windows are placed symmetrically, being distances of 4 and 6 m apart.

The entrance to the fort is located in the middle of the north side. The gateway itself is 1.5 m wide and 2.3 m high and is set within a frame of dressed dark purple sandstone. Above the doorway is a lintel set within a large semi-circular arch. Directly above the gateway, there is a sandstone stone bearing an inscription (since 1986 this has been removed, its current location is unknown). The gateway is fairly narrow, only 1.5 m wide at the entrance, but it opens out to 2 m on the interior, where it leads into a vaulted entrance passage. The passageway is roofed with a pointed vault and opens into a central courtyard, which is roughly square (8.8 x 8.1 m). In the centre of the courtyard, there is a square hole, 0.6 m per side, which gives access to a bottle shaped cistern.

The north range of rooms contains three doorways, including the entrance hall, which is in the middle. At the west end of this range, there is a doorway with a wooden lintel, which leads into a long room (6.4 m) covered with a vault, running east to west.

Three rooms are opening onto the west side of the courtyard, as well as a staircase to the first floor in the northwest corner. To the south of the staircase, there is an entrance covered with a shallow stone arch, leading into a narrow room 4.25 m long and 2.2 m wide. South of this there are two narrow rooms, each of identical size and design. The south side of the courtyard leads into three rooms: an iwan in the centre – facing the entrance, and two large rooms on either side. The east side of the courtyard opens onto two rooms, with vaults, running east-west. The room nearest the southeast corner is 4.4 m long and 3.3 m wide, whilst the other room is of the same length, but only 2.9 m wide. In the northeast corner, there is a second flight of stairs leading to the upper rooms.

The first floor is reached by either one of two staircases, facing each other across the courtyard. Each staircase is 1.2 m wide and 4.4 m long and is covered by an arch. The surface of the upper floor is composed of flint cobbles, bordered by dressed limestone blocks. The rooms on the upper floor do not appear to have been vaulted and the remains of wooden roofing beams can be seen in a few places.

The west range contains two shallow rooms located to the south of the stairs. Both of these rooms have walls that have been capped with a layer of small stones set in mortar, implying that they may not have had permanent roofs. The south range of rooms is a complex arrangement, centred on a wide arched iwan with a shallow recessed niche in the centre of the south wall. The niche is lined with plaster and has a scalloped design in the concave hood. Like the niche directly below, this was also probably a prayer room. To the east of the iwan, the arrangement is less complicated, comprising one rectangular and one square room.

There are two cisterns at Fassu‘a, the nearest of which lies 40 m from the entrance of the fort. Both reservoirs are of similar size and are laid out parallel to each other, connected by a low wall, 7.5 m long, joining the south ends of both. The cisterns are built of semi-dressed sandstone and large blocks of flint and are plastered internally. The plaster is similar to that used in the fort and also resembles that found on other Ottoman reservoirs.

Half a kilometre to the west of the fort there is a pile of flint rubble standing at a height of 2 m. Close inspection reveals the remains of rough stone walls, built on a square plan (3 m per side). In the middle of the east side, there is a hole, 0.7 m wide, which gives access to the interior of the structure. To the northeast of this structure, approximately 750 m away there is another structure of a similar design. From their high position above the fort, it is assumed that these structures were beacons to guide pilgrims to the fort.

From the historical evidence it appears that soon after the fort’s construction it fell into disrepair; all the visitors, from 1825 onwards, have referred to it as a ruined structure. There are two features of particular interest in the design of this fort. Firstly, it is notable that there are two prayer rooms one on the first floor, and the other on the ground floor. The second feature of interest is the complex of structures to the west of the upper prayer room, these may have functioned as a latrine and ablutions area, even, perhaps, a small bathhouse.

Although the fort at this site is of relatively recent origin, the site appears to have considerable antiquity. During his pilgrimage in 1326, Ibn Battuta passed from Ma‘an in Syria to ‘Aqaba al- Suwwan (the pass of flint), which can certainly be identified with Faussu’a based on the flint strewn ground in this area. The difficulties of the route in this place are recalled by Evliya Celebi, who referred to the site simply as Aqaba. Celebi states that it was very difficult to ride the animals at this point, so everyone had to dismount and walk on the stony ground. He also comments that many of the pilgrims were robbed as they passed this point, presumably in the pass leading down towards Mudawarra, 10 hours distant.

Up until the mid-18th century, there is no indication of a fort at Fassu‘a, the first time a fort is mentioned at this site is in the account of Mehmed Edib, who visited in 1779 and observed that a fort and fountain had been built by Osman Pasha. Edib observes that the fort is located in a waterless valley strewn with stones and sand, 13 hours south of Ma‘an.

In 1825 the fort was visited by Muhamad ‘Ali’s inspector, who referred to the fort as Qal‘at al-Qasba. The inspector notes that the fort is in a ruinous condition, with two of the walls destroyed and indicates that he has written a letter to the shaykhs of Ma‘an, asking them to undertake some renovation. He also notes the presence of two cisterns, each measuring 40 30 cubits with a depth of 10 cubits. Although both cisterns were in a good condition, they did not collect much water.

In May 1910 the site was visited by Musil, who describes arriving at ‘the small ruined fortress of Faso‘a, north of which are situated two artificial rain pools still partly filled with water’. Musil’s time at the site was cut short due to the behaviour of his camels, which, very thirsty on arrival, rushed to the cisterns and then ran about searching for pasture until they had eaten everything in sight.